Aerial view of a solar array in Austin, Texas. Roschetzky Photography/Shutterstock

Angela Picciariello, Senior Research Officer, ODI

This blog post is also available at ODI.

The Paris Agreement sets a goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, preferably close to 1.5°C. To achieve this, global emissions need to be reduced – and quickly. They must drop to 26 GtCO2e in 2030, which means roughly halving current levels over the next 10 years. That’s why now, more than ever, we need to find new and more effective ways to decarbonise how we produce and consume our goods and services.

As we build up to COP26 in Glasgow in November, it is vital that we plan effective ways forward. So, what sectors should we prioritise in our decarbonisation efforts? Energy is key, and a sector which – as our new research shows – city governments can play an influential role in shaping.

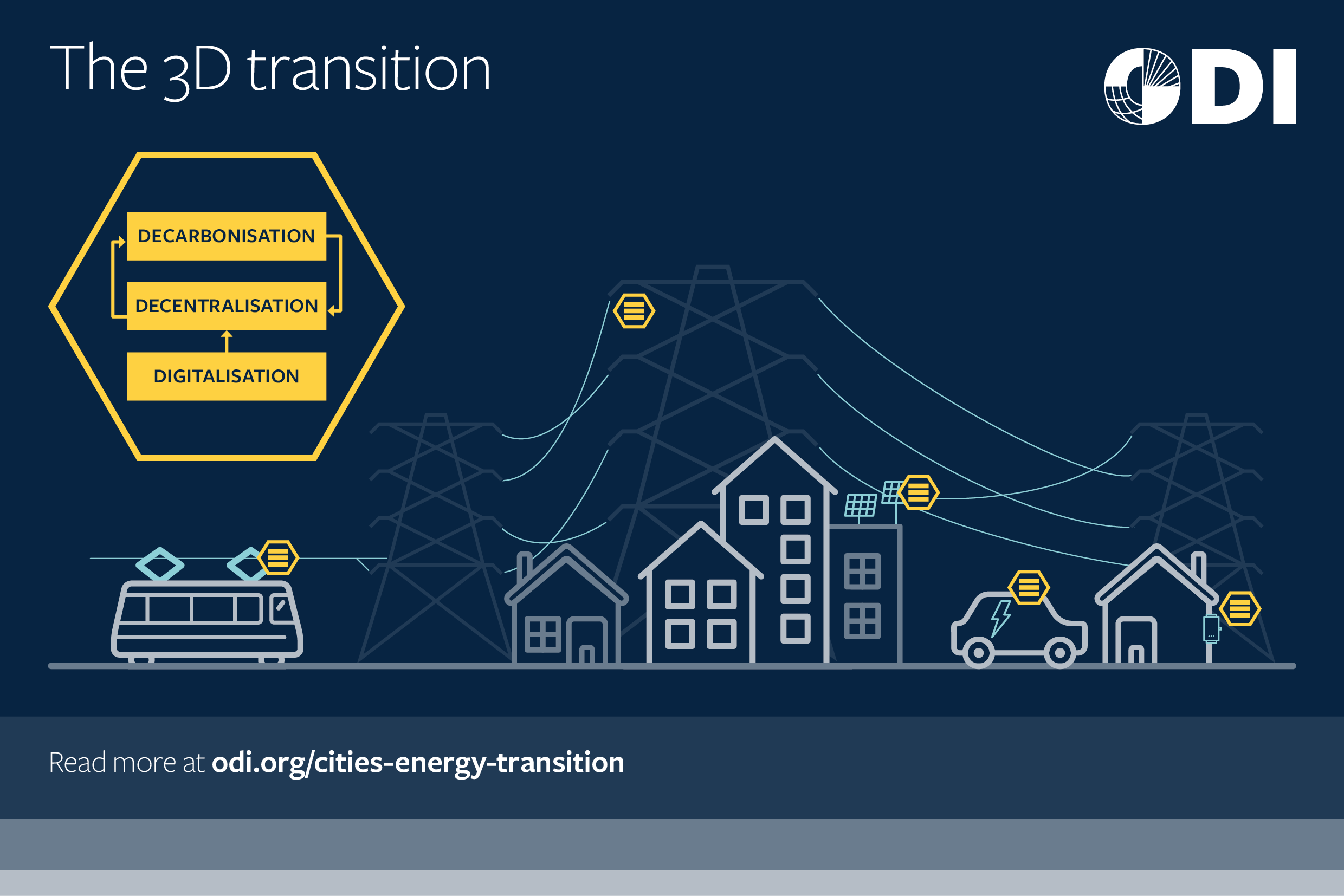

The “3D transition”: decarbonisation, decentralisation, and digitalisation

Our energy systems have a fundamental role to play in accelerating decarbonisation. In 2018, the power sector accounted for nearly two-thirds of global emissions growth. And this should not be too surprising, if we consider that 90% of the global population is currently connected to the electricity grid and the global energy system is still highly carbon intensive, with coal, oil and natural gas meeting 85% of all energy needs.

Lignite Power Plant at sunset with cloudy sky in Neurath, Germany. R.classen/Shutterstock

And yet, what is generally known as the energy transition – a transition toward cleaner, less emission-intensive energy systems – is already happening in a number of places. The decarbonisation of electricity is occurring through a mix of strategies, many of which increasingly rely on decentralisation and digitalisation as well. These are collectively known as the “3Ds”.

Decentralisation happens when electricity is increasingly generated from small-scale power sources that are distributed throughout an electricity grid, often closer to where the demand for electricity is. Rooftop solar panels, for example, can help meet the electricity needs of the buildings where they are installed.

Decentralisation is often, but not always, being accompanied and facilitated by the third D, digitalisation. For example, digital tools make it possible to know in real-time the situation of the energy system, and potentially enable flexibility measures (for example, turning off the dishwasher or boiler when the system experiences high electricity demand or the solar panels or wind turbines are not generating electricity), or improved forecasting to contribute to planning and operations.

While the 3D transition is already happening throughout the world, its pace and form varies by country. Places like Costa Rica are leaders in terms of energy decarbonisation, but not as much when it comes to decentralisation and digitalisation.

Chucas hydroelectric power plant in Costa Rica. Joshua ten Brink/Shutterstock

Senegal, meanwhile, is a leader in decentralisation through its deployment of microgrids. The country is stepping up its digitalisation capacity to allow these decentralised grids to function more effectively.

Villagers socialise under bright lights after dark following the installation of a solar power grid paid for by the community in Niomoune, Senegal. Pascal Maitre/Panos Pictures

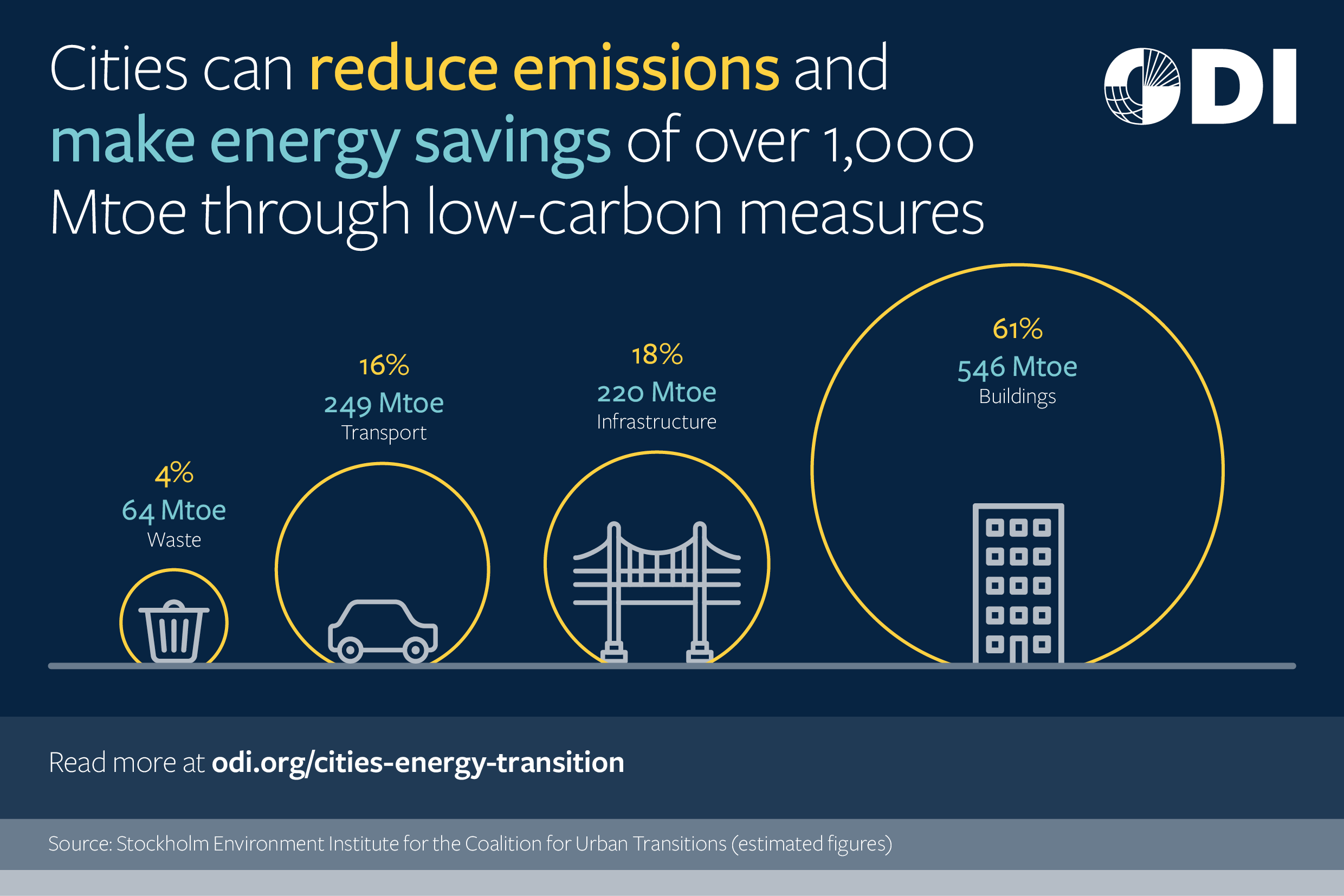

The decarbonising potential of cities

Cities are particularly strategic areas to target because they are the locus of much energy demand, and because local governments can catalyse 3D transitions. Cities are where the 3D ‘megatrends’ are increasingly converging, and a number of local governments are showing immense climate ambition.

In South Africa, for example, Durban has developed a geospatial map to allow residents to identify cost and savings opportunities for installing rooftop solar PV systems. In Texas, Austin has included in its latest published city strategy a comprehensive set of goals for decarbonisation, energy efficiency, demand-side response, and technology and storage. These include increasing the share of renewables in the electricity mix from 38% (2018) to 65% by the end of 2027.

Low cost township houses fitted with solar heating panels in Verulum in Durban, South Africa. Lcswart/Shutterstock

Grid decarbonisation is not always easy to achieve…

Notwithstanding their ambition, cities will have a hard time achieving grid decarbonisation on their own. Decarbonising electricity grids will require nationally led efforts to steer power systems through different stages of clean power deployment – including widespread deployment of variable (intermittent) renewable energy sources. Each stage will present different challenges.

For example, at an early stage of the transition, the biggest challenge may simply be installing more renewable capacity. At a later stage, the bigger share of renewable energy sources connected to the grid will require more flexibility to operate them, and often some market restructuring to enable such flexibility.

… but cities can play an important role

National policy and regulatory reforms will be needed to navigate these transitions. But in designing these reforms, national policy-makers should not overlook the important role of local governments in making them a success. Across the various stages of the transition, city governments can help national governments to address the specific challenges they face. This support can take different forms.

Direct partners in power sector planning

City governments can provide a detailed understanding of local barriers and opportunities for siting distributed renewables or improving energy efficiency in buildings. They can also advise and facilitate local 3D planning, for example by involving citizens in consultations and decisions. These efforts can help ensure the success of so-called “prosumer” decentralisation models, where citizens become both electricity consumers and producers.

Ireland’s 2019 Climate Action Plan is a great example of how national targets (such as retrofitting hundreds of thousands of homes) can be designed with local implementation in mind. The Plan contains a detailed national sectoral roadmap that relies on direct partnership with local authorities, who have all established Climate Action Regional Offices (CAROs) responsible for the delivery of action plans.

Streamline implementation efforts

The ability to develop and deploy new power system infrastructure depends on local permit rules, municipal procurement policies, zoning ordinances and other bylaws. These important local responsibilities are often overlooked in broader policy studies. City governments can help streamline implementation in various ways, including by:

- Improving permitting procedures and bolstering staff to conduct inspections

- Fast-tracking permitting for electric vehicle charging infrastructure

- Running ongoing public awareness campaigns

- Maintaining registries of certified installers of clean distributed energy resources.

For example, Shenzhen has retrofitted bus and taxi fleets by providing city-wide infrastructure, financed in part by national government.

Cars and other electric vehicles charging at a station, one of the biggest in the country. Qilai Shen/Panos Pictures

Encourage local initiatives

City governments can encourage local firms, councils and civil society organisations to install microgrids and support neighbourhood-wide renewables deployment. For example, community bulk buying programmes can accelerate the adoption of local renewable energy sources.

Leveraging the potential of local governments to support the energy transition

When it comes to the interactions between national and local governments, bidirectional support is needed to progress the clean energy transition.

For cities to be able to play a proactive role in a national 3D energy transition, national governments need to involve city-level governments early in their own planning processes. This may involve:

- Conducting a joint assessment of the skills and finance required by local governments, in order to implement complementary measures

- Enhancing ‘vertical’ coordination between national and city level governments, and ‘horizontal’ coordination across different municipal agencies

- Establishing data sharing frameworks between national and city actors.

The city of Munich is a good example of how task forces can be set up effectively to allow for horizontal coordination across different agencies. The city owns and operates its utilities jointly across telecommunications, transportation, energy, water and waste. This way, it can retain revenues and make investments in the future of these businesses. It can set up new task forces, for instance on electric vehicles, to ensure operational siloes are overcome.

The Solar City Seoul project set a target of reaching 1 gigawatt in rooftop solar power by 2022. This includes all municipal buildings and 1,000,000 homes. The scheme, partly funded by government subsidies, is expected to create 4,500 jobs and is a great example of successful ‘vertical’ coordination.

Solar panels on an apartment in Seoul.

Kim Jihyun/Shutterstock

The way forward

The emerging trends of decentralisation and digitalisation can support the transition to cleaner and more sustainable energy systems.

Indeed, the combination of low-carbon technologies and strategies with decentralised energy solutions and digital tools is already happening in a number of places, especially in global megacities.

But this type of transition does come with various challenges, which city governments can help national governments to overcome. This is especially true where local knowledge and more fluid regulatory frameworks are needed. At the same time, national governments need to support local governments, mainly by involving cities in planning processes early on and creating the right legal frameworks for them.

As we rapidly electrify sectors, decarbonisation of electricity must be a top priority in the global and national agendas. Production and consumption patterns need to adapt quickly. The built environment in cities has huge potential to accelerate decarbonisation and bring new electrified infrastructure into our energy systems.